There are many terrible things in the world but the clothing market is not one of them. The entire sector is dynamic and creative, distributing essential goods to the globe in ways that appeal to the infinite variety of human desire and economic means to buy. Opportunities to buy are ubiquitous in both the physical and digital worlds.

In my grandmother’s early life, her mother sewed her dresses from flour sacks and repaired sock holes to make them last for many years. Today, even the poor have large wardrobes for every occasion.

It’s an amazing transformation.

Moreover, over the last decades, clothing has emerged as a great outlier in the general price trend. We pay less for clothing today than we did 25 years ago. It’s worth understanding why.

When we talk about prices, we make reference to the Consumer Price Index (CPI). In reality, there is no such thing. Yes, the government assembles it and, yes, it reports it. Economists love it and follow it closely. But, in the end, it is a statistical fiction, something that exists in the math but not in real life. It’s not like a yard stick or the sea level. Nothing is priced by it. The CPI speaks of general trends but it masks underlying realities.

In real life, even in a controlled economy like the U.S., prices for various sectors, and even within sectors, move in ways that defy aggregation. Some are up, some are down, and prices for the same goods can be different even within the same geographic space. Stores next door to each other sell the same goods for completely different prices.

Over the holiday season I was out and about looking at shoes, coats, suits, ties, and so on. It’s not just men’s clothes. Women’s clothing prices seem particularly chaotic. It’s to the point that when you look at a price, you can’t really anticipate whether it will be $50 or $500 or even $5,000 (yes, I recently saw a $5,000 dress on a rack in Chicago).

Then you go to second-hand shops and get the real shock. Stuff that costs $100 retail can be $1. Sites like eBay are driving down prices to rock bottom. I can pick up a gorgeous suit for $20. Then there are the online discount shops. Comparing prices across them can play tricks on your mind. I go to WalMart and I can’t believe my eyes: some clothes seem cheaper to buy than to wash.

A price index shields our eyes from all this pricing chaos. Pity the economic planner who uses the CPI to inform policy: he is dealing with a mental invention.

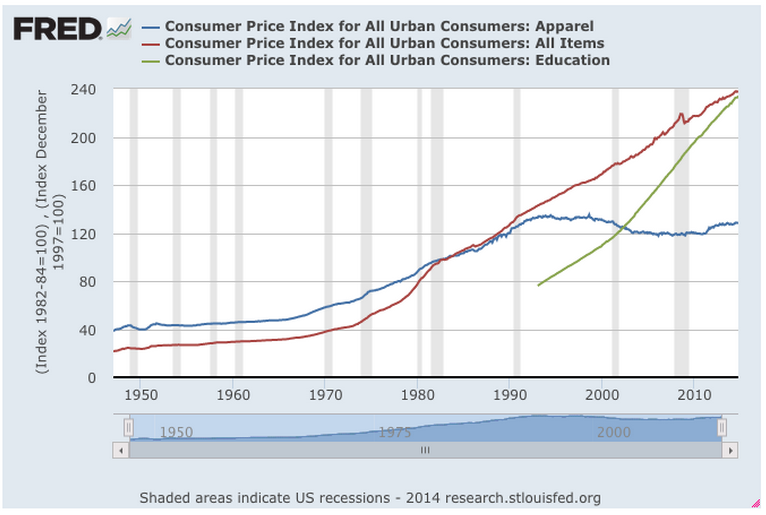

Still, we use such indices to look at the sweeping trends. Looking at the Federal Reserve statistics for prices (collected by people employed by the Department of Labor to follow these things), we see that clothing prices on average are at the same level they were a quarter of a century ago. This is despite massive Fed money expansion, and large price increases in sector like education and health care.

Price pressure has been generally up, particularly for sectors hobbled by government intervention. Clothing, which lives in a market mostly free of government subsidies and manipulations, breaks the mold.

After tracking the overall CPI generally for 20 years from 1970 forward, something changed in 1990 that stopped the price increases and then generally put downward pressure on prices for the next 20 years. In this graph, the red line is the CPI. The green line is education. The blue line is clothing in general (again, in the real world, there is plenty of variation in these aggregated indices).

What changes occurred over the course of the 1990s and 2000s that brought this wonderful trend about? There was the reform of China’s economy, which turned first to textile manufacturing. Then there was the collapse of socialism in Eastern Europe, which opened up massive new human resources and intensified producer rivalry. India and Mexico became huge producers in textiles. Those changes vastly increased the global trade in clothing.

The shift was gigantic. In 1991, American clothing accounted for more than half of what we bought. Today only 2.5% is manufactured in the U.S. In the same period until 2012, 75% of the jobs in clothing manufacturing were lost. It was the “great depression” for the American industry, but this was matched by the biggest gift to American consumers ever.

Then there was the growth of Internet commerce, which allowed consumers to compare prices with much greater efficiency and opened up markets even more. Also, during these same years when copyright and patent were heavily enforced in nearly every sector, they have never applied to clothing. Knock offs are now way of life. Yes, there is trademark but even here, it is mostly unenforceable and gray markets abound.

At every stage in this process since 1990, people were crying out about impending disaster. The U.S. is losing its textile manufacturing base. We are shipping jobs overseas. Deflation is ruining the profitability matrix in clothing Slave labor is replacing paid labor. Crazy dot coms are foisting shoddy products on the world and driving out legitimate retail shops. Big box stores are gobbling up everything. Pirate products are flooding the world.

And so on. If you followed all the policy debates and business-page headlines, you would swear that nothing good was happening.

And yet look at the results. Go out shopping this weekend and you see how clothing is a wonderfully vibrant market, with luxury shops thriving alongside discount shops, online retailers competing with brick-and-mortar shops, franchises booming even as local stores and mission thrifts do well too.

Brand names still sell at top dollar, even as knock-off products with similar names at a fraction of the price are doing well too. In the end, the clothing sector is a model of how markets should work. The seeming chaos, the unpredictable and spontaneous changes that are global in scope, have ended up producing a glorious result, with no coordination coming from the top.

What is a price? It is a proposed point of agreement between a buyer and seller. The proposal is the key. It is not a marching order. Past prices represent deals done in history. Current prices represent possible deals in the future. Prices embed vast information about perceived realities: resource availability, consumer demand, cultural biases and habits, speculations about the future. The price is also an amazing tool. It provides an objective basis for accounting and the assessment of profit and loss. Without prices, real prices rooted in real market experience, we’d be lost.

And when you look at the active market for clothing, you discover another fact: it is impossible to centrally plan prices for anything. In a vibrant market, they fluctuate in uncountable and unpredictable ways. They are as diverse and unplanned as the human mind itself. And yet consider all the ways in which government attempts to set and manipulate prices in other sectors: minimum wage, rent control, medical services, mails, and every government service. None of it makes sense.

Controlling prices by central command is as preposterous as yelling instructions to a flock of birds. If you succeed in getting your way, it is only because the birds have been caged and denied the freedom to move. Or maybe they are dead.

No one institution controls the price of clothing. That’s a wonderful thing, and a major reason why the market works. If this is chaos, let us have more of it. Let us look and learn, and adopt that model for all the truly troubled sectors of economic life.

Back in the day, too many of my favorite people in the LP got into this mind set that dressing for the occasion of our national conventions was counter revolutionary. As if looking clean and polished was a tool of the oppressors. They should have taken a look at the snappy uniforms worn by the Black Panthers or the suits worn by Nation of Islam. They made an impression on the Normals that they meant business. — Angela Keaton

Just a tip for other ‘frugal’ folks out there: Thrift stores in rich tourist towns are AWESOME. In Sun Valley Idaho, the local library was wholly supported by a thrift store. There are folks up there who never wear the same outfits twice, let along for more than one season. I got an $800 Bogner ski suit for $20. There are thrift stores in Aspen, Carmel, every upscale town, I’m sure.

Treasure hunt!

Just a tip for other ‘frugal’ folks out there: Thrift stores in rich tourist towns are AWESOME. In Sun Valley Idaho, the local library was wholly supported by a thrift store. There are folks up there who never wear the same outfits twice, let along for more than one season. I got an $800 Bogner ski suit for $20. There are thrift stores in Aspen, Carmel, every upscale town, I’m sure.

Treasure hunt!

@jeffreytucker if you haven’t seen this TED talk yet, you’ll love it: http://www.ted.com/talks/johanna_blakley_lessons_from_fashion_s_free_culture?language=en

Custom clothing: the next great advancement. Bespoke everything for the common person.

Custom clothing: the next great advancement. Bespoke everything for the common person.